Good morning…

God’s timing astounds me. On June 17th at 2:09 pm, I received the email initiating yesterday’s post, a post about a man in Jacksonville who was touched by our past post, as he grieved the loss of his nephew to a drug overdose.

I am not kidding you. Less than two hours later, at 3:49 pm on June 17th, I got another email. “I wanted to share this article with you,” a loyal subscriber wrote. So I clicked on the link and found these tender words.

******

How to Support Someone Grieving An Overdose Loss – JUNE 17, 2019 BY MARGARET M. LINNEHAN

I have experienced deep and painful grief from the death of many loved ones in my life. My husband died of a sudden heart attack in his sleep. My younger sister died of cancer. I lost both of my sons — my younger one to an accident, and my older one who died of a substance use disorder.

My husband’s, younger son’s and sister’s deaths were considered socially acceptable to grieve. The loss I felt when I lost my older son to an overdose was painful in multiple ways, and different than any other grief. I still remember the horror of him not showing up to pick me up. Calling a Lyft and coming home and seeing his light on upstairs and the music playing. The sinking feeling of realizing something was horribly wrong. Climbing the steps and finding him dead, and knowing he had lost his battle with opioid addiction.

There was shame and guilt for being relieved that his battle was over, and feeling the judgment of society as my son’s death was considered socially marginal — as if he somehow deserved or wanted to die because of his addiction.

Drug addiction is a disease. Our society, however, does not accept it as a disease; we treat people with substance use disorders as though they can somehow control their behavior. Believe me, my son did not want to be in bondage to opioids.

My son had been using opioids off and on for over 10 years. He had many years in recovery where he was not taking anything. There is the belief as a parent that your child has finally turned the corner and you are done with the disease. There is a rollercoaster of hope, loss and pure terror at the grip the drugs have on your child.

Processing a Special Kind of Grief from Substance Use

As a parent of a child that has a substance use disorder, you go over in your mind what you missed, what you could have changed — “if only” plays out in a thousand ways. And, if you are not hard enough on yourself, you know what is whispered about your child. You know the judgment from others; you feel it emanating from them. It is not only in their words — it is in their body language, a nuance or in a thoughtless, hurtful statement.

You are embarrassed and humiliated by not only the lengths your child goes to feed their addiction, but the extent you go to as a parent to try and help them. You’re embarrassed by the things you forgive, such as theft, lying, and mental terrorism, that are used on you by this person using opioids.

You go the distance because of love and guilt. If my child had cancer, would I ignore it or pretend it didn’t exist? Did I cause this; am I responsible for their addiction?

For me, there was a sense of strange relief when my child passed away from an overdose, knowing your child is out of pain — relief that you are no longer living in a nightmare, wondering where they are or if they are dead, waiting, wondering if you will see them again. Then there is guilt for feeling this way when your loved one is gone. It is all part of the process and being human.

I do not regret spending money or time to try to help my son find a cure to his disease. My only regret is that I did not understand substance use sooner. I am also glad that I ignored everyone who told me to just “cut him loose.” I am not angry at them; I know they did not understand it, either.

How You Can Help Support Those Who Have Lost a Loved One to Addiction

If you have not lost someone to substance use or an overdose death, how could you know? Below are some things I have learned losing my son to an overdose, and what I believe is helpful and what is not helpful. We need to help teach people how to treat us at different crossroads in our lifetime.

- Please don’t avoid the subject. He was my son and I loved him and I want to talk about him. I don’t mind discussing the good and the bad. The good in that I have beautiful memories of my son, his quick wit and humor, his kindness towards others, his intelligence and his musical and cooking abilities. My son was a wonderful person. The substance use was not wonderful, and that was also a part of the history. Please just listen and sit with me if I need to talk about it.

- Put a card in the mail, send flowers, drop off food, come to his memorial or share a memory of him. Do not run away or turn your back because you do not know what to say.

- Please don’t judge me, because I feel enough shame and guilt myself. I ask myself if I did everything I could. Could I have done more? Is it my fault my son died? Was I a bad parent? I am hard enough on myself; I do not need anyone else passing judgment on me as a parent. I am no different than you — I did band practice, car pools, packed lunches, went on vacation and loved my son. Addiction is a disease. You would not judge me if my son had died of cancer; please don’t judge me as a parent because he died of an overdose.

- I know there were times that I was angry with my son. I had enough and said some things to him that I did not mean. Have you ever done that with your adult child? For me, this is compounded by the years spent dealing with substance use and the frustration and grief of feeling that your child is not there.

- Don’t tell me to “get over it” or that I need to “move on.” Do not tell me how long to grieve, as if his life didn’t count for anything. I need to grieve in my own way and my own time.

- Please do not treat his death as if it was marginal. It was not. It was a life and he had a light that went out. My heart hurts when something is said without thinking of the impact it has on everyone who is grieving him.

- Please don’t “ghost” me. To have a friend for 14 years who suddenly does not return your calls or emails because they do not want to be associated with the stigma of substance use is painful. It causes more pain — you now are not only grieving your son, but the loss of someone you thought was a friend. It multiplies the pain. Brenee Brown calls it “flying debris” when you are going through a difficult time. It feels so relevant to losing a loved one to an overdose.

- I know you are trying to cheer me up, but often I am not up for social situations while grieving. I will be angry at times, want to be alone or want to cry. Grief does not follow a formula; it is a rollercoaster and you are along for the ride. You do not always see the dips coming. If I leave abruptly it means I need to go home, please do not try and stop me. Please understand that during those times, I need to be alone.

- Be mindful of my grandchildren, as they are hurting, too. They lost their father, and when insensitive remarks are made, it hurts them deeply. It impacts their grieving, and they are just children. If you can’t say something nice about their loved one, don’t say anything.

- Please don’t bring up my sons’ death to overdose in a social situation, especially with people I don’t know. If I want to talk about it, I will. While the person means well, many people react differently to this kind of death. It can change the energy in the room and I find myself having to tell “my story” when I am not up for it, or wasn’t ready to share it with everyone. Let me take the lead.

- If you have had a similar problem with someone in your family who has a substance use issue or you lost someone close to substance use, talk about it — don’t hide it. Let’s work toward destroying this stigma together.

- Put a Black Balloon up on March 6. That day is Black Balloon Day in memory of anyone you know who has died from substance use. Help keep their memories alive and help those who are still battling this awful disease.

Most importantly, for me, is to allow myself time to grieve. I aim to surround myself with people who truly love me and understand what I am going through. If anyone you know is struggling with this type of grief, be a light for them in the darkness.

I step out of the way to witness God ministering tenderly, person to person, at the perfect time, with an undeniably palpable presence. Healing without meeting. Understanding without seeing. Comforting without face to face connection. We are in intimate relationship with a God who whispers in so many wonderfully wild ways, “I am real. I am here. I am surrounding you.”

Where can I go from your Spirit?

Where can I flee from your presence?

If I go up to the heavens, you are there;

if I make my bed in the depths, you are there.

If I rise on the wings of the dawn,

if I settle on the far side of the sea,

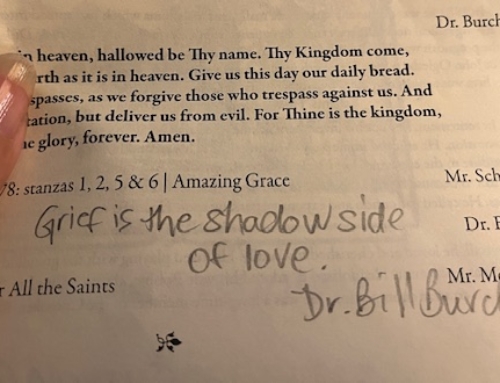

even there your hand will guide me,

your right hand will hold me fast (Psalm 139:7-10, NIV).

…Sue…